Climate Science 3

But does it REALLY matter?

A couple of degrees doesn't sound much - the temperature goes up and down much more than that each day! On the other hand, a couple of degrees on top of the already record heat of the extreme summer days can be disastrous. The point is that we already have 'extreme' conditions, whether hot, cold, wet, dry, but by adding more energy to the climate system (in the form of heat) we drive those extremes further. It is heat energy that drives climate systems and, as a result of the added greenhouse effect, the Earth is accumulating extra heat at the rate of about half a watt for every square metre. (This is explained in more detail in the Climate Physics section.) That might not sound a lot, but it adds up to the energy equivalent of setting off nearly half a million Hiroshima sized nuclear bombs EVERY DAY. That energy mostly goes into the oceans, from where it drives weather systems. The effects are not uniform around the Earth, some places get hotter, some get wetter, some dryer - and storms and cyclones get stronger.

The results of Cyclone Haiyan Nov 2013 in the Philippines

The results of Cyclone Haiyan Nov 2013 in the Philippines

Storms and cyclones are driven by heat from the ocean. Rising currents of warm moist air carry energy out of the oceans into the climate system. The more energy available the stronger the storms or cyclones. Perhaps rather curiously, the climate models don't predict more cyclones, but rather, stronger and so more damaging ones.

The number of record breaking 'weather events' around the world is increasing. Normally records (of any sort) should become harder to beat with more time, but extreme weather records are falling at an increasing rate! This must be telling us something.

Anyone in south-east Australia is all too aware of the increasing risk of bushfires linked to more and more over 40 degree days.

The number of record breaking 'weather events' around the world is increasing. Normally records (of any sort) should become harder to beat with more time, but extreme weather records are falling at an increasing rate! This must be telling us something.

Anyone in south-east Australia is all too aware of the increasing risk of bushfires linked to more and more over 40 degree days.

Curiously enough, despite what some people have claimed, even the exceptional freezing winter conditions that have occurred in the northern hemisphere in recent years are actually due to global warming.

The simple version is that warmer conditions in the Arctic push the (still very cold) air higher - and therefore further south - bringing freezing conditions to lower latitudes than normal. (For the more complicated versions see, for example, this article published by the Royal Society or this one in Scientific American for December 2012.)

The simple version is that warmer conditions in the Arctic push the (still very cold) air higher - and therefore further south - bringing freezing conditions to lower latitudes than normal. (For the more complicated versions see, for example, this article published by the Royal Society or this one in Scientific American for December 2012.)

This is a picture of Syrian farmers. As is obvious, their land is very dry. In fact they are in the midst of the worst drought in hundreds of years. A recent article in Scientific American was titled "Climate Change Hastened Syria's Civil War. Human-induced drying in many societies can push tensions over a threshold that provokes violent conflict" They are not saying the drought directly caused the terrible war in Syria, but they are pointing out that the drought, "exacerbated to record levels by global warming, pushed social unrest in that nation across a line into an open uprising in 2011. The conflict has since become a major civil war with international involvement." Not to mention causing enormous floods or refugees to Europe.

There is a lot of unrest in the world. When drought, floods and famine are added, it is a recipe for disaster.

There is a lot of unrest in the world. When drought, floods and famine are added, it is a recipe for disaster.

Extreme weather events cost lives and cause devastation, they always have. In the developed nations we have got better at preparing for such conditions, but despite this the world-wide toll of climate related natural disasters is rising, not falling. However, as bad as it is, extreme weather is not the worst consequence of global warming/climate change. It is just the early warning signals. But it is the long term consequences that give us most reason for concern, because we are ....

Heading toward a different Earth

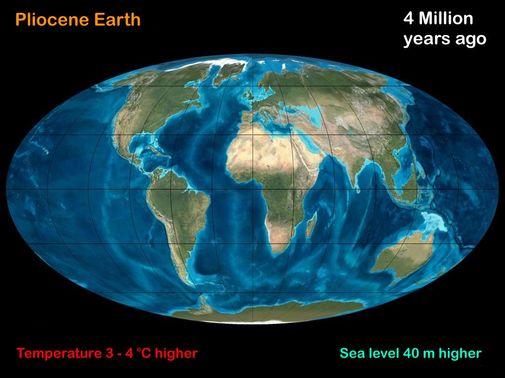

When seen in the light of the '500 Million years' graph on the Climate 2 page, it is clear that there is a very real danger that we are heading back to conditions not seen since the Pliocene, several million years ago. It was a very different Earth.

It is difficult to picture just how different the Pliocene Earth was. This image shows some of the differences we could expect - much less snow at the poles (hence the sea level rise of around 30 to 40 metres), much of Europe and Asia flooded, and of course all present day coastal cities under water. What is not so obvious on the drawing is that many ecosystems would have moved several hundred kilometres toward the poles due to the hotter temperatures.

Once things stabilized it would certainly be a habitable Earth. But it would be a very different one and the BIG problem is of course that the changes involved in getting from what we have now to the new Earth would be disastrous for civilisation. Imagine the problems of creating, or maintaining, ports when sea levels are continually changing - not to mention the slowly drowning coastal cities. At present something like one in every hundred people on the planet live less than 1 metre above sea level - that's about three times the whole population of Australia. If we think we have mass migration problems at present ... just imagine!

However, the real problem is that much of the world's crop lands are at low levels and the combination of loss of crops and the inevitable increasing population would cause huge problems. Furthermore, with increasing temperatures, crop lands can turn into deserts in just decades. And while new regions might eventually become arable, that is a very much slower process. The Antarctic might eventually become habitable, but it will take centuries to establish new viable ecosystems where there has been nothing but ice and bare rock for millennia.

It is difficult to picture just how different the Pliocene Earth was. This image shows some of the differences we could expect - much less snow at the poles (hence the sea level rise of around 30 to 40 metres), much of Europe and Asia flooded, and of course all present day coastal cities under water. What is not so obvious on the drawing is that many ecosystems would have moved several hundred kilometres toward the poles due to the hotter temperatures.

Once things stabilized it would certainly be a habitable Earth. But it would be a very different one and the BIG problem is of course that the changes involved in getting from what we have now to the new Earth would be disastrous for civilisation. Imagine the problems of creating, or maintaining, ports when sea levels are continually changing - not to mention the slowly drowning coastal cities. At present something like one in every hundred people on the planet live less than 1 metre above sea level - that's about three times the whole population of Australia. If we think we have mass migration problems at present ... just imagine!

However, the real problem is that much of the world's crop lands are at low levels and the combination of loss of crops and the inevitable increasing population would cause huge problems. Furthermore, with increasing temperatures, crop lands can turn into deserts in just decades. And while new regions might eventually become arable, that is a very much slower process. The Antarctic might eventually become habitable, but it will take centuries to establish new viable ecosystems where there has been nothing but ice and bare rock for millennia.

Of course all this won't happen in our lifetime, but it might in the lifetime of our children and grandchildren. Are we really happy enough to condemn future generations of humanity to potentially catastrophic continual change? In fact are we prepared to take that risk? There are huge uncertainties about the time scale involved. But we are changing the atmosphere at a rate faster than any known natural event, except comet impacts or massive volcanic eruptions and the like - both of which resulted in mass extinctions on a huge scale. Perhaps it will be centuries before sea levels rise many metres, but it could also be within this century. We just don't know. Are we really prepared to take that risk?

So what is happening at the poles? (Because that's what's driving sea level rise)

An iceberg collapses, West Greenland. Carsten Egevang/ARC-PIC.COM

An iceberg collapses, West Greenland. Carsten Egevang/ARC-PIC.COM

In the Ice Ages (over the last one million years or so) so much water was locked up as ice at the poles that sea levels were about one hundred metres lower than today's shore lines. On the other hand, for most of the last few hundred million years there has actually been little ice at the poles and so sea levels have been up to one hundred metres higher than today's coasts. The amount of ice locked up at the poles (and to a lesser extent in glaciers around the world) makes a HUGE difference to life on Earth.

This is why scientists are trying very hard to understand the dynamics of ice sheets - the huge layers of ice that lie on Antarctica and Greenland.

It is known that the rate of ice sheet melting at both poles is rapidly increasing, but there are large uncertainties around the way the rate will increase as the planet warms further. Ice melts both from the top (due to atmospheric warming) and the bottom (due to ocean warming). The amount of melting that results from atmospheric warming is somewhat predictable - from the basic physics and studies of what is actually happening.

The really difficult problem is to understand the bottom melting. It is not just a case of predicting how much ice warmer water will melt. Much of the land ice in Antarctica, for example, is based on rock which is actually below sea level. Once water starts to flow into the region under the ice it could fairly suddenly make the ice sheets unstable and increase the rate at which they are sliding into the ocean in unpredictable ways.

The IPCC predictions of sea level rise were made at a time when these sorts of processes were not at all well understood and so did not take them into account. This is why the IPCC predictions of something less than a metre of sea level rise have to be seen as very much a lower limit. More recently, scientists have been saying that we could see well over a metre, or more, by the end of the century.

This is why scientists are trying very hard to understand the dynamics of ice sheets - the huge layers of ice that lie on Antarctica and Greenland.

It is known that the rate of ice sheet melting at both poles is rapidly increasing, but there are large uncertainties around the way the rate will increase as the planet warms further. Ice melts both from the top (due to atmospheric warming) and the bottom (due to ocean warming). The amount of melting that results from atmospheric warming is somewhat predictable - from the basic physics and studies of what is actually happening.

The really difficult problem is to understand the bottom melting. It is not just a case of predicting how much ice warmer water will melt. Much of the land ice in Antarctica, for example, is based on rock which is actually below sea level. Once water starts to flow into the region under the ice it could fairly suddenly make the ice sheets unstable and increase the rate at which they are sliding into the ocean in unpredictable ways.

The IPCC predictions of sea level rise were made at a time when these sorts of processes were not at all well understood and so did not take them into account. This is why the IPCC predictions of something less than a metre of sea level rise have to be seen as very much a lower limit. More recently, scientists have been saying that we could see well over a metre, or more, by the end of the century.

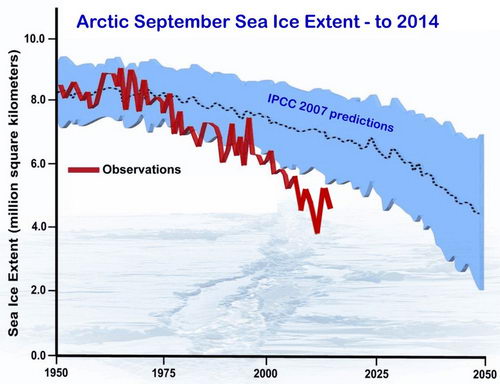

It is somewhat easier to see what is happening with sea ice. Each summer the extent of ice coverage reduces and can be measured by satellites. Over the last few decades there has been a noticeable decline in the amount of sea ice left in the Arctic summer. This is not a steady effect, some summers have more ice than the preceding one, but on average the amount of ice is getting less. In fact it is getting less at a faster rate than many of the scientists expected. This graph shows the rate of loss of ice predicted by various computer models (and quoted by the IPCC) as well as the actual loss. Clearly things are happening more rapidly than the models expected.

The real worry is that summer sea ice is now only about half what it has been over the last several thousand years - and heading for total loss in summer in a few decades. [And it has continued getting less since 2014-new graph to come!]

We mentioned earlier that the Arctic is warming at a faster rate than most of the rest of the Earth. This is partly due to the 'dark water' feedback effect mentioned on the Climate 1 page, as well as the fact that there is more land area (which warms faster than water) in the northern hemisphere. This is certainly one of the reasons for the greater than expected decline in Arctic summer sea ice. But of course the dark water feedback does not only effect the Arctic. By warming the waters of that region it also warms the whole of the oceans because of the huge ocean currents that link the polar waters to the equatorial waters. Indeed the 'Thermohaline circulation', the great ocean current that links all the oceans of the world is itself in danger of being changed by the warming, and freshening, waters of the Arctic. If that were to stop or be significantly altered it would have catastrophic consequences on the world's climate.

The real worry is that summer sea ice is now only about half what it has been over the last several thousand years - and heading for total loss in summer in a few decades. [And it has continued getting less since 2014-new graph to come!]

We mentioned earlier that the Arctic is warming at a faster rate than most of the rest of the Earth. This is partly due to the 'dark water' feedback effect mentioned on the Climate 1 page, as well as the fact that there is more land area (which warms faster than water) in the northern hemisphere. This is certainly one of the reasons for the greater than expected decline in Arctic summer sea ice. But of course the dark water feedback does not only effect the Arctic. By warming the waters of that region it also warms the whole of the oceans because of the huge ocean currents that link the polar waters to the equatorial waters. Indeed the 'Thermohaline circulation', the great ocean current that links all the oceans of the world is itself in danger of being changed by the warming, and freshening, waters of the Arctic. If that were to stop or be significantly altered it would have catastrophic consequences on the world's climate.

Meltwater from the ice sheet surface is drained through a moulin. West Greenland. Konrad Steffen/CIRES, University of Colorado

Meltwater from the ice sheet surface is drained through a moulin. West Greenland. Konrad Steffen/CIRES, University of Colorado

Now of course sea ice melting doesn't affect sea level rise directly - the ice is already in the sea. However, that dark water feedback effect results in the water becoming warmer and that starts to impact on the land ice, particularly the Greenland glaciers which are slowing sliding into the sea. There is a lot of evidence that not only are they melting from the top (due to the warmer atmosphere) but they are also melting from below due to the warmer water creeping in underneath. This not only melts the ice, but lubricates it, enabling it to slide into the sea more quickly. Of particular concern is that some parts of the Greenland ice sheet appear to be grounded on rock that is below sea level. This means that once water starts to flow in, the ice may start sliding into the sea very quickly.

It is more difficult to assess the rate at which land based ice in Greenland is melting, but the best estimates suggest that it could be considerably higher than was thought some years back. Some studies have suggested that global warming of around 1.5 - 2 degrees would be enough to melt the whole of the Greenland ice sheet. This would take a few centuries, but would result in an added 7 metres of sea level rise - on top of the rise due to the Antarctic and glacial melt, as well as the thermal expansion discussed earlier.

It is more difficult to assess the rate at which land based ice in Greenland is melting, but the best estimates suggest that it could be considerably higher than was thought some years back. Some studies have suggested that global warming of around 1.5 - 2 degrees would be enough to melt the whole of the Greenland ice sheet. This would take a few centuries, but would result in an added 7 metres of sea level rise - on top of the rise due to the Antarctic and glacial melt, as well as the thermal expansion discussed earlier.

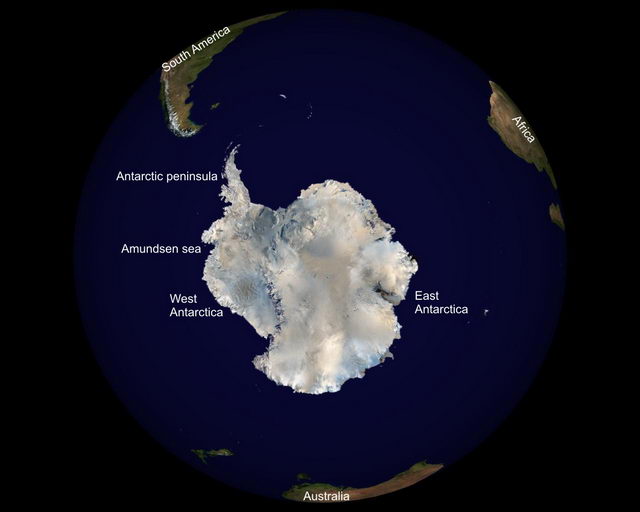

Things are different in the Antarctic

Most of the northern polar region is sea - albeit frozen sea. It is mostly surrounded by land which absorbs sunlight and warms more rapidly than sea. On the other hand, Antarctica is a huge continent surrounded by sea. This is why what is happening in Antarctica seems rather different to what is going on in the Arctic.

One notable difference is that while sea ice is disappearing in the Arctic, it seems to be increasing in the Antarctic. Another is that the amount of snow falling (and accumulating) on the Antarctic continent may even be increasing.

Paradoxically, both these phenomena seem to be the result of a warming climate. (Although some parts of Antarctica are warming more slowly than much of the Earth.) Warmer water evaporates more readily than cold and hence there is more moisture in the atmosphere. More moisture, more rain and snow - hence the increase in snow accumulation.

There are several reasons for the increased sea ice. One is that because of the increasing run-off of fresh water from melting glaciers, the sea is becoming less saline. Fresh water freezes at a warmer temperature than salt water - hence the waters around Antarctica are freezing more easily, creating more sea ice. As well, the glaciers are 'calving' faster - tipping huge icebergs into the ocean. A third factor is possibly to do more with the Ozone hole than global warming, but as a result of the Ozone hole there has been a marked increase in the winds around Antarctica in the last several decades and this helps to create more ice in cold conditions.

One notable difference is that while sea ice is disappearing in the Arctic, it seems to be increasing in the Antarctic. Another is that the amount of snow falling (and accumulating) on the Antarctic continent may even be increasing.

Paradoxically, both these phenomena seem to be the result of a warming climate. (Although some parts of Antarctica are warming more slowly than much of the Earth.) Warmer water evaporates more readily than cold and hence there is more moisture in the atmosphere. More moisture, more rain and snow - hence the increase in snow accumulation.

There are several reasons for the increased sea ice. One is that because of the increasing run-off of fresh water from melting glaciers, the sea is becoming less saline. Fresh water freezes at a warmer temperature than salt water - hence the waters around Antarctica are freezing more easily, creating more sea ice. As well, the glaciers are 'calving' faster - tipping huge icebergs into the ocean. A third factor is possibly to do more with the Ozone hole than global warming, but as a result of the Ozone hole there has been a marked increase in the winds around Antarctica in the last several decades and this helps to create more ice in cold conditions.

The real concern, however, is what is happening to the Antarctic land ice sheets, as that is by far the most important long term factor. It is certainly clear that they are melting faster. Some studies have found that, at present, the rate of snowfall is just about replacing the melt-water, but this is not certain, and in any case the melting is increasing at a rapid rate and will soon well and truly exceed the snowfall rate.

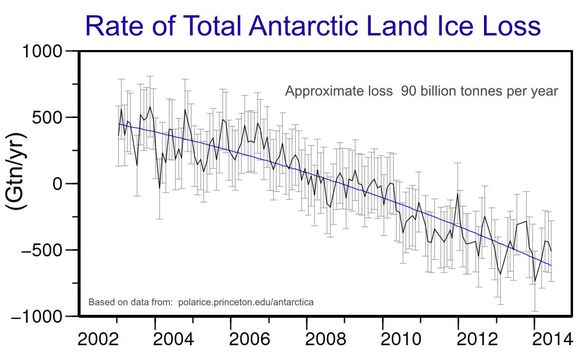

Satellites flying over the Antarctic measure the strength of gravity extremely precisely. As the ice melts and runs into the sea the gravity drops ever so slightly. From these measurements the amount of melting can be estimated. This graph shows a typical set of results of such studies. While in some parts of the Antarctic net ice loss is almost zero, in other parts it is much faster.

This graph is for the total Antarctic land ice loss. Note that the rate of loss is getting steeper - that is what is really concerning. (Gtn = billion tonnes)

[The trend has continued to get steeper since 2014 - new graph too come!]

Satellites flying over the Antarctic measure the strength of gravity extremely precisely. As the ice melts and runs into the sea the gravity drops ever so slightly. From these measurements the amount of melting can be estimated. This graph shows a typical set of results of such studies. While in some parts of the Antarctic net ice loss is almost zero, in other parts it is much faster.

This graph is for the total Antarctic land ice loss. Note that the rate of loss is getting steeper - that is what is really concerning. (Gtn = billion tonnes)

[The trend has continued to get steeper since 2014 - new graph too come!]

What does melting ice do to sea levels?

Clearly, the big question is: what will all this melting ice mean for sea levels? Answering this question is not easy. Over the course of human history polar ice has been relatively stable - because the climate has been relatively stable. Therefore we have no direct experience of large sheets of ice melting. Some evidence can be gained by looking at the geological evidence however. The most recent large scale melting was of course when the Earth came out of the last ice age.

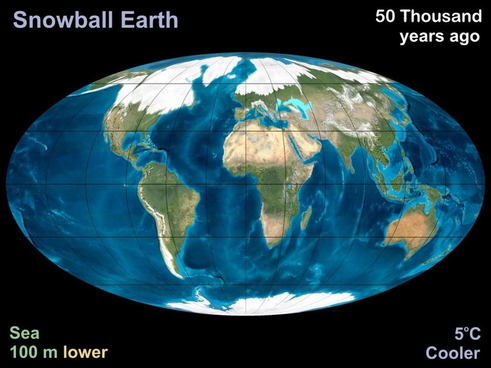

This diagram illustrates what the Earth would have looked like near the end of that ice age. Huge areas of the northern hemisphere were covered with ice and snow and sea levels were around 100 metres lower that at present. Global temperatures were a few degrees lower. Clearly a few degrees can make a huge difference to the amount of water locked up as ice. As we have seen, however, it took around 5000 years for the Earth to go from a full ice age to the current inter-glacial.

This diagram illustrates what the Earth would have looked like near the end of that ice age. Huge areas of the northern hemisphere were covered with ice and snow and sea levels were around 100 metres lower that at present. Global temperatures were a few degrees lower. Clearly a few degrees can make a huge difference to the amount of water locked up as ice. As we have seen, however, it took around 5000 years for the Earth to go from a full ice age to the current inter-glacial.

Our problem now is to figure out how rapidly polar ice might melt given the increased greenhouse effect warming from the extra CO2 we have put into the atmosphere. While we can be fairly sure that if the climate warms several degrees the long term melting will mean tens of metres of sea level rise - as in the Pliocene era - the question is how fast this will occur and whether we can reverse it by cutting emissions.

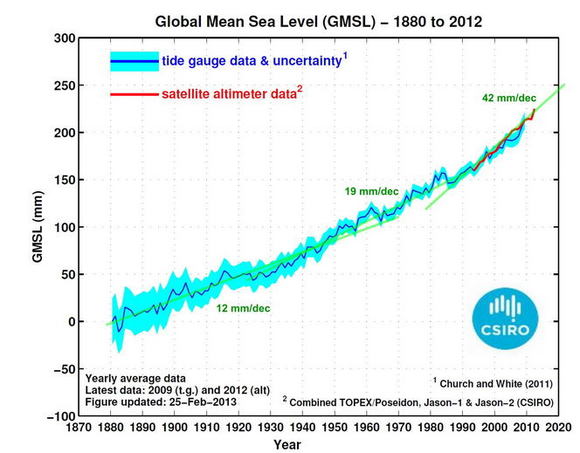

If we look at the current rate of sea level rise we can get some clues. In this graph based on CSIRO data as well as that based on satellite measurements we can see that the rate of sea level rise (SLR) has been increasing. Earlier last century it was around 12 mm/decade, mid century around 19 mm/dec, but over the last couple of decades it has increased to over 40 mm/dec - which is 0.4 metre per century.

The problem of course is that the rate is increasing. Even at the current rate we would have to expect around 40 cm rise by 2100, but clearly as the rate is increasing it will be much more than that.

The ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica are huge. It takes a long time to start warming them, but once they get to around zero degrees they start to melt much faster. This is one of the factors that makes it very hard to predict future rates of melting and hence sea level rise.

The problem of course is that the rate is increasing. Even at the current rate we would have to expect around 40 cm rise by 2100, but clearly as the rate is increasing it will be much more than that.

The ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica are huge. It takes a long time to start warming them, but once they get to around zero degrees they start to melt much faster. This is one of the factors that makes it very hard to predict future rates of melting and hence sea level rise.

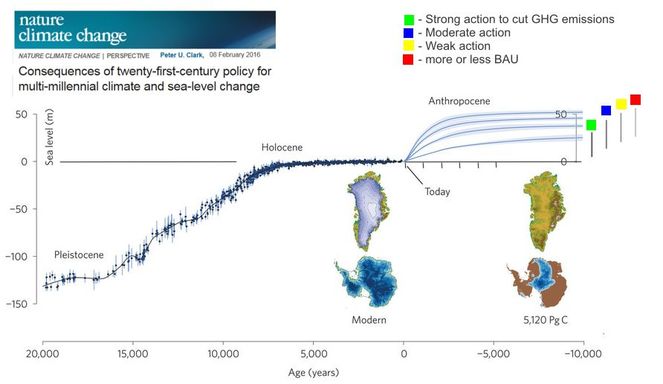

A number of researchers have attempted to model melting and hence sea level rise. A recent study in Nature Climate Change estimated the consequences of our current policies on the rate of SLR over the next millennia. Here is a simplified version of their results.

They found that if we take very strong action to cut CO2 emissions (green) we will probably end up with a SLR of around 25 m in the long term (a few thousand years) whereas with weak action (red) it would be over 50 m.

Maybe in a thousand years people will adjust, but the big problem is that there will be continually rising seas in the shorter term.

They found that if we take very strong action to cut CO2 emissions (green) we will probably end up with a SLR of around 25 m in the long term (a few thousand years) whereas with weak action (red) it would be over 50 m.

Maybe in a thousand years people will adjust, but the big problem is that there will be continually rising seas in the shorter term.

The past can tell us about the future

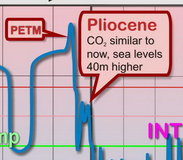

We have already seen that the geological period known as the Pliocene could well be an indication of where the Earth's climate is heading, as that was the last time the CO2 level was about the same as now - although we will be well and truly exceeding it soon unless drastic cuts are made to emissions. But there is another period that could well be relevant to our future as well. It is called the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, or PETM for short, it occurred about 56 million years ago and was a sudden (in geological terms) spike in temperatures. You can see both the PETM and the Pliocene on the 500 million years graph on the Climate 2 page. A clip from that graph is shown here also.

We are sometimes told that climate change is natural, it has happened in the past and is happening again - so all is well, the planet survived previous change. Unfortunately the messages from past climate changes actually tell us exactly the opposite - all will be far from well. Yes, the planet survived, but many forms of complex life did not. And human life and civilisation could be said to be the most complex yet.

The sharp increase in temperature in the PETM was the result of a large natural release of CO2, most likely from volcanic activity, which drove strong warming. That warming caused further amplifying feedbacks – the release of yet more carbon (as CO2 and methane, CH4) from thawing permafrost in the Arctic and frozen methane clathrates in sea-floor sediments.

The amount of CO2 released in the PETM was huge – about equivalent to burning all the fossil fuel reserves we have today. However, it was released over a very long time – several thousand years. We are currently adding CO2 to the atmosphere at a rate about ten times faster. Furthermore, the CO2 stayed in the PETM atmosphere for over 100,000 years – an indication of how long it takes for CO2 to be absorbed back into the biosphere. Scientists who have studied this PETM warming say that it indicates that the climate is more sensitive to added CO2 than most of the climate models suggest. While models suggest something like 3 degrees rise for doubling CO2, with a possible range from 2 to 6 degrees, the PETM studies suggest it could well be at the higher end of that range.

Other effects of the PETM warming are also evident in the geological records of the time. From sediments washed into the sea, it is clear that there was a lot of erosion on land. This would have been the result of more intense storms, droughts and floods. It is also clear that ecosystems migrated long distances toward the poles seeking cooler climates. Many species of plants and animals became extinct as they became trapped by oceans. Many larger mammals became notably dwarfed – probably due to heat stress or lack of nutrition.

We are sometimes told that climate change is natural, it has happened in the past and is happening again - so all is well, the planet survived previous change. Unfortunately the messages from past climate changes actually tell us exactly the opposite - all will be far from well. Yes, the planet survived, but many forms of complex life did not. And human life and civilisation could be said to be the most complex yet.

The sharp increase in temperature in the PETM was the result of a large natural release of CO2, most likely from volcanic activity, which drove strong warming. That warming caused further amplifying feedbacks – the release of yet more carbon (as CO2 and methane, CH4) from thawing permafrost in the Arctic and frozen methane clathrates in sea-floor sediments.

The amount of CO2 released in the PETM was huge – about equivalent to burning all the fossil fuel reserves we have today. However, it was released over a very long time – several thousand years. We are currently adding CO2 to the atmosphere at a rate about ten times faster. Furthermore, the CO2 stayed in the PETM atmosphere for over 100,000 years – an indication of how long it takes for CO2 to be absorbed back into the biosphere. Scientists who have studied this PETM warming say that it indicates that the climate is more sensitive to added CO2 than most of the climate models suggest. While models suggest something like 3 degrees rise for doubling CO2, with a possible range from 2 to 6 degrees, the PETM studies suggest it could well be at the higher end of that range.

Other effects of the PETM warming are also evident in the geological records of the time. From sediments washed into the sea, it is clear that there was a lot of erosion on land. This would have been the result of more intense storms, droughts and floods. It is also clear that ecosystems migrated long distances toward the poles seeking cooler climates. Many species of plants and animals became extinct as they became trapped by oceans. Many larger mammals became notably dwarfed – probably due to heat stress or lack of nutrition.

The oceans of the PETM were also affected by the warmth and the extra CO2 dissolved in the sea water. Coral reefs were largely lost due to both the warmth and increased acidity. Sea life was severely reduced as water depleted of oxygen became lifeless, producing hydrogen sulphide (‘rotten egg gas’) as living organisms died out. Plankton, the small organisms at the bottom of the food chain, died out leaving many of the larger fish to starve.

If climate changes occur slowly, over tens of thousands of years, ecosystems can adapt or migrate. As well, the added CO2 can gradually be absorbed by rocks and seafloor shells. But the PETM changes were clearly too rapid for many systems. The problem, of course, is that current changes threaten to become much more rapid even than those of the PETM.

In the last decade or so scientists have discovered a lot about the PETM, and similar events. But a lot still remains uncertain. It is crucial that more research is supported in this area so that we can get a better picture of what may well indicate the future results of our ‘artificial’ emissions of CO2. What is clear, however, is that the warming in the PETM resulted in changes that lasted for more than 100,000 years and were catastrophic for many living systems on land and in the ocean. It is a clear warning that what we are currently doing to our atmosphere could also have disastrous results.

If climate changes occur slowly, over tens of thousands of years, ecosystems can adapt or migrate. As well, the added CO2 can gradually be absorbed by rocks and seafloor shells. But the PETM changes were clearly too rapid for many systems. The problem, of course, is that current changes threaten to become much more rapid even than those of the PETM.

In the last decade or so scientists have discovered a lot about the PETM, and similar events. But a lot still remains uncertain. It is crucial that more research is supported in this area so that we can get a better picture of what may well indicate the future results of our ‘artificial’ emissions of CO2. What is clear, however, is that the warming in the PETM resulted in changes that lasted for more than 100,000 years and were catastrophic for many living systems on land and in the ocean. It is a clear warning that what we are currently doing to our atmosphere could also have disastrous results.

The Danger of Tipping Points

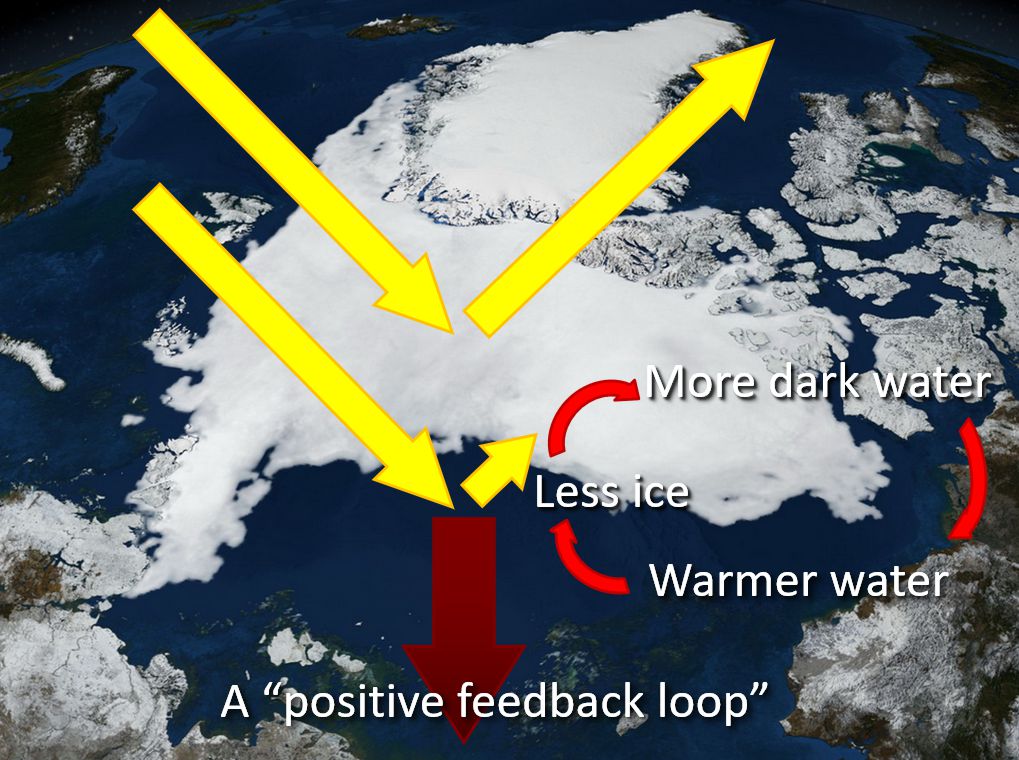

Scientists are concerned that if the Earth's temperature goes over a certain point, processes will start that will continue to warm the Earth regardless of whether we manage to reduce the greenhouse gases. What that point is, is hard to determine, but it could well be within the range of 1.5 to 2 degrees. This is the result of "positive feedback" effects. A simple example is the melting Arctic ice. Ice reflects something like 95% of the sunlight that falls on it, but ocean water reflects very much less. So the more the ice melts, the more warmth the ocean absorbs - and the more the ice melts.

|